Restoring the Marsh

Discover the National Park Service’s and our efforts to save, restore and stabilize the marsh.

Dyke Marsh Is Disappearing

Dyke Marsh will be gone by 2035 without action, predicts the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The marsh is losing 1.5 to two acres a year and the rate of erosion is accelerating.

In a 2013 update to their 2010 landmark study, USGS reported, "We ultimately conclude that Dyke Marsh presently is in its late stages of failure as a freshwater tidal marsh system. Bathymetry data confirm that tidal creeks are stripping sediment from the marsh, rather than aggrading it onto the marsh. Erosion is fragmenting the marsh and dismantling tidal creek networks by stream piracy. In the absence of human efforts to restore the equilibrium between marsh and tide, and equilibrium to the other natural forces acting on this wetland, Dyke Marsh likely will continue to accelerate its degradation, erosion, and fragmentation until it is gone. This likely will occur prior to 2035 AD."

"Dyke Marsh is "the nearest thing to primeval wilderness in the immediate vicinity of the city."

The Problem

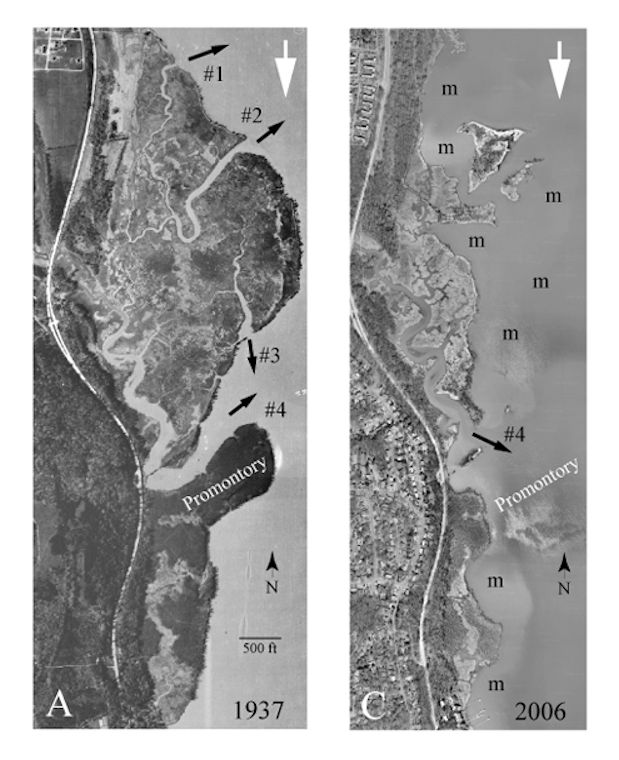

In 1940, Dyke Marsh was around 180 acres in size. By 2010, it was around 53 acres, said USGS. The USGS scientists wrote, “Analysis of field evidence, aerial photography, and published maps has revealed an accelerating rate of erosion and marsh loss at Dyke Marsh, which now appears to put at risk the short term survivability of this marsh.”

The USGS 2010 study also had these findings:

• Dredging of sand and gravel from 1940 to 1972 was a strong destabilizing force, transforming it from a net depositional state to a net erosional state. Dredging removed around 101 acres or 54 percent of the 1937 marsh.

• Erosion is both continuous and episodic. The changes caused by dredging have made the marsh subject to significant erosion by storm waves, especially from winds traveling upriver. Damaging storms occur approximately every three years.

• Mining or removing the promontory on the southern end of Dyke Marsh removed the geologic wave protection of the south marsh that existed back to at least 1864 and altered the size and function of the tidal creek network.

• “This freshwater tidal marsh has shifted from a semi-stable net depositional environment (1864–1937) into a strongly erosional one . . . The marsh has been deconstructed over the past 70 years by a combination of manmade and natural causes. The marsh initially experienced a strong destabilizing period between 1940 and 1972 by direct dredge mining of the marsh surface. By 1976 the marsh had entered a net destructive phase, where it remains at present.”

• The minimal protection needed to protect and enhance natural deposition includes a wave break in the location of the former promontory.

The U.S. Geological Survey study is titled Analysis of the Deconstruction of Dyke Marsh, George Washington Memorial Parkway, Virginia: Progression, Geologic and Manmade Causes, and Effective Restoration Scenarios and was written by Ronald J. Litwin, Joseph P. Smoot, Milan J. Pavich, Helaine W. Markewich, Erik Oberg, Ben Helwig, Brent Steury, Vincent L. Santucci, Nancy J. Durika, Nancy B. Rybicki, Katharina M. Engelhardt, Geoffrey Sanders, Stacey Verardo, Andrew J. Elmore and Joseph Gilmer. It is on the USGS website here.

Historic Imagery Viewer Shows Changes over Time

Fairfax County has an imagery viewer that can help people understand the extent of the wetland in the past and provide context for marsh restoration. For more information, click here.

Why Should Dyke Marsh Be Restored?

Rare: Dyke Marsh is a rare freshwater, tidal wetland along the Virginia shoreline of the Potomac River in the Washington, D. C., area, one of the most highly-valued habitats in the region. It is one of the most significant temperate, climax, riverine, narrow-leafed, cattail marshes in the U. S. National Park system nationwide. The marsh started forming between 5,000 and 7,000 years ago with the youngest part located on the northern extension. It is unusual because much of it has survived in a large metropolitan, heavily developed area.

Habitat Loss Means Species and Opportunities Lost: Over the years, there has been a decline in many species and some have become extinct in Dyke Marsh. Dyke Marsh supports the only known nesting population of marsh wrens (Cistothorus palustris) in the upper Potomac tidal zone, a species once found in many of the marshes that lined the Potomac River. In 1950, 87 singing males were counted. In 2012, two nests were found. In 2015, one marsh wren has been seen. The least bittern, which also nests in Dyke Marsh, is on the Virginia’s threatened list. A restored Dyke Marsh can provide more habitat for more birds, fish and other wildlife, more plants, more biodiversity and more opportunities for recreation, education and scientific study.

Restoration Can Buffer Some Flooding, Surges: Wetlands can stem flooding. A one-acre wetland can store about three acre-feet of water or one million gallons, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (An acre-foot is one acre of land, about three-fourths the size of a football field covered with one foot of water.) Preserving and rebuilding natural defenses against storms is one of the most cost-effective and sustainable ways to protect communities and natural resources. Virginia has lost almost half of its wetlands.

Cleaner Water: The restoration of Dyke Marsh can help improve water quality in the Potomac River and the Chesapeake Bay because wetlands filter out pollutants and sediment loads from stormwater runoff. The Potomac provides drinking water to over five million people in the Washington area. Minimizing contaminants that might be missed during water treatment procedures can improve human health.

Rich in Diversity: Dyke Marsh has 300 known species of plants, 6,000 arthropods, 38 fish, 16 reptiles, 14 amphibians, over 230 birds. Since at least the late 1800s, it has been the only site in the upper Potomac River with a breeding population of marsh wrens, but in 2015, whether these birds bred in Dyke Marsh is unclear. The marsh has a state-threatened breeding population of least bitterns. A restored marsh can support and expand that biodiversity.

Congress Stressed Preservation: The U. S. Congress designated Dyke Marsh in 1959 by law as part of the National Park system “so that fish and wildlife development and their preservation as wetland wildlife habitat shall be paramount.” Congress reaffirmed its support and the marsh’s significance by approving House Resolution 701 in 2009 and Senate Resolution 297 in 2010. In 1974, Congress authorized the Corps of Engineers to assist NPS in restoring the “historic and ecological values of Dyke Marsh.”

Human Caused: Extensive dredging of almost half the marsh from 1940 to 1972 destabilized the marsh. People inflicted the damage; people should fix it.

"In 1959, this body [the U.S. House of Representatives] passed legislation that designated Fairfax County's Dyke Marsh as a protected ecosystem for the purpose of promoting fish and wildlife development and preserving their natural habitat. Now, at the time, Dyke Marsh was being dredged for commercial purposes. They were going deeper and deeper to get gravel. They were ruining the ecosystem. For those who live in the Washington metropolitan area or may be visiting the Washington metropolitan area, if you go down the George Washington Parkway toward Mount Vernon, right after the city of Alexandria, you will see Dyke Marsh. . . Dyke Marsh is about 500 acres. It's preserved. It's a beautiful area. You can see bald eagles; you can see great blue herons. You can see snapping turtles; a whole lot of bullfrogs. There aren't a lot of places left in the Washington area where you can see this unless you go to the zoo."

“Chincoteague, Dyke Marsh, and the Great Dismal Swamp are natural treasures of Virginia. In recent years, disasters like Sandy and crises like sequestration and the government shutdown have significantly impacted our ability to maintain the Commonwealth’s natural resources. I welcome this much-needed federal investment and will continue working to preserve the Commonwealth's beautiful waters and lands for future generations to enjoy.”

“Dyke Marsh is one of the most significant temperate, tidal, freshwater, riverine marshes in the National Park system. It is a remnant of the tidal wetlands that once lined the Potomac River."

"Dyke Marsh is a magnificent little oasis”

FODM Supports Restoration

The Friends of Dyke Marsh have advocated for restoration of Dyke Marsh since the organization's founding in 1976. FODM believes that a restored marsh can restore coastal resiliency, buffer the area against some storm activity, restore more habitat for birds, fish and other wildlife; restore more native wetland plants and other biota; create a healthier overall ecosystem, and if restored, provide more opportunities for research, nature study and educational, recreational and other nature-oriented activities. A restored Dyke Marsh can be a more robust outdoor classroom for hundreds of students of all ages and a natural laboratory for scientists and others.

Restoration Funds Were Available

Thanks to broad support, funding was available, primarily from two sources:

1. MWAA Mitigation Funds

On March 27, 2013, the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA) made available to the National Park Service (NPS) $2.5 million for construction of a "promontory structure breakwater." The breakwater would be designed to replicate the historic promontory in the southern end of the marsh that protected Dyke Marsh, but was removed by Smoot Sand and Gravel. The USGS study maintains that a replacement promontory would provide a buffer against storms and flooding, encourage accretion and deposition of sediment and restore ecosystem services that benefit the Potomac River, the Chesapeake Bay and the community. The airport funds represent compensatory mitigation for impacts of a runway extension, an airport landing safety area, required to meet Federal Aviation Administration safety standards.

NPS and MWAA received 80 public comments, almost all of which were supportive. Among those who sent supportive comments were Congressmen Jim Moran and Gerry Connolly; Sharon Bulova, Chair, Fairfax County Board of Supervisors; William Euille, Mayor of Alexandria; the Northern Virginia Conservation Trust; the National Parks and Conservation Association; the Nature Conservancy (Virginia); the Potomac Conservancy; the Audubon Society of Northern Virginia; the Audubon Naturalist Society; the Mount Vernon Council of Citizen Associations and the Virginia Conservation Network.

2. Department of Interior, $25 Million in Resiliency Funds

U.S. Secretary of Interior Sally Jewell on October 24, 2013 came to the Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve and announced the award of a $24.9 million grant to restore Dyke Marsh, part of President Barack Obama’s Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Strategy and Climate Action Plan to build resilience by restoring natural features along shorelines and to protect communities from storms. Virginia U.S. Senator Tim Kaine, a staffer for U.S. Senator Mark Warner, Eighth Congressional District Congressman Jim Moran and Alexandria Councilwoman Allison Silberberg attended.Secretary Jewell said, “What we witnessed during Hurricane Sandy was that our public lands and other natural areas are often the best defense against Mother Nature. By stabilizing marshes and beaches, restoring wetlands, and improving the resiliency of coastal areas, we not only create opportunities for people to connect with nature and support jobs through increased outdoor recreation, but we can also provide an effective buffer that protects local communities from powerful storm surges and devastating floods when a storm like Sandy hits.”The announcement is on the Department of the Interior website and a video is here.

The NPS Restoration Plan

The National Park Service (NPS) published the final Dyke Marsh Restoration and Long-term Management Plan on October 9, 2014 in the form of an environmental impact statement (EIS). Among other objectives, the plan would restore wetlands and ecosystem functions and processes and protect the remaining wetland. Restoration would also increase the resilience of the marsh, provide a buffer to storms and control flooding, states the EIS. NPS maintains that their restoration plan would bring beneficial impacts to the marsh's hydrology, sediment transport, vegetation and wetlands and stabilize erosion.

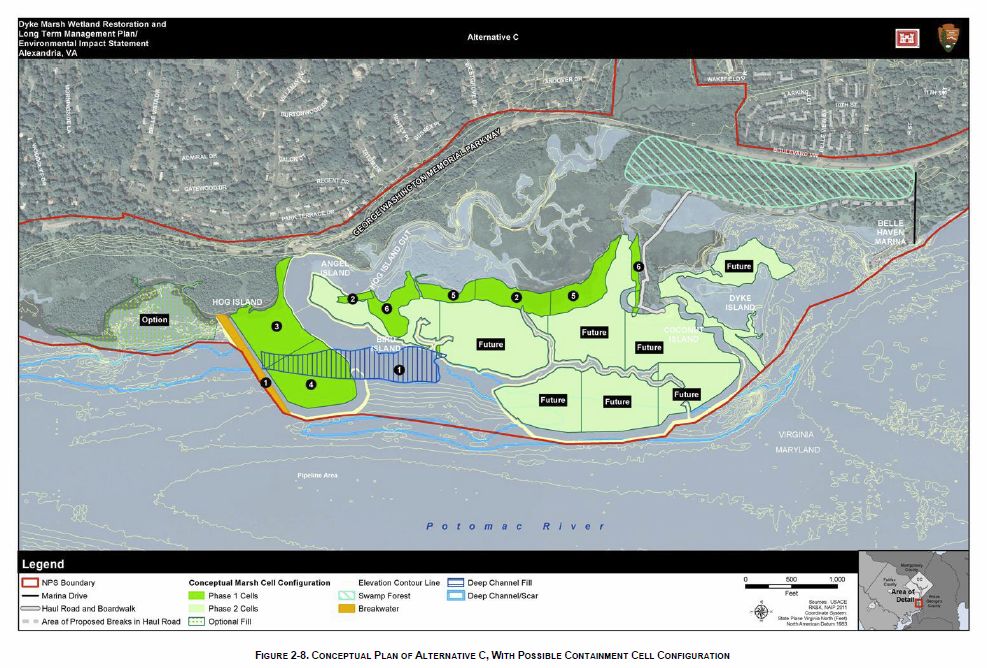

NPS’s plan or preferred alternative is “alternative C,” the “fullest possible extent of wetland restoration,” an approach which would restore up to 180 acres of wetland habitats in stages. The Friends of Dyke Marsh support alternative C. NPS would restore the marsh in a phased approach “up to the historic boundary of the marsh and other adjacent areas within NPS jurisdictional boundaries, except for the area immediately adjacent to the marina.”

In phase one, NPS would build a breakwater in the southern part of the marsh to replicate the promontory removed by dredgers and identified by USGS as critical to protecting and restoring wetland habitat. "Phased restoration would continue until a sustainable marsh is achieved . . . .," says the plan.

Other steps:

• fill the deep channels created by dredging;

• restore emergent marsh within the area of the historic promontory;

• build containment cells within the historic boundary. "The location of these cells would be prioritized based on the most benefits of the specific locations could provide to the existing marsh. . . ."

• restore marsh along the edge of existing marsh to wherever the water is less than four feet deep; and

• install breaks in the Haul Road to "reintroduce tidal flows west of the Haul Road" and to restore the swamp forest.

Why is Dyke Marsh Significant?

FODM has published a flyer outlining the significance of Dyke Marsh and why we should care about the health of this valuable resource.

First Steps in Restoration

On September 28-29, 2015, National Park Service (NPS) and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE) officials met to begin the design of the restoration of Dyke Marsh under a NPS-COE interagency agreement. Officials estimate the design phase will take at least 12 months. Once the design is completed, NPS will have to get several permits before starting construction of the first phase, the breakwater on the southern end of the marsh to replicate the promontory removed by the dredgers. Once NPS obtains necessary permits, construction will take around two years.

In December 2015, the Corps of Engineers created a website for the project: http://www.nab.usace.army.mil/Missions/CivilWorks/dykemarshrestoration.aspx. COE has posted some history, facts, a map, photographs, tentative schedule and the conceptual restoration plan.

COE officials have said that they hope to award a contract to build the promontory in 2017 and that they might start building a containment cell in 2017 as well. COE officials also expect substantial construction to be completed in 2019, depending on funds.

In early 2016, Corps staff conducted a bathymetric survey in Dyke Marsh (photo, right by Ed Eder).

In May, using a barge (photo left by Ned Stone), the Corps staff conducted dilatometer tests in Dyke Marsh to measure different layers of soil and soil strength for building the foundation of the breakwater in the south marsh. Building a breakwater is expected to be phase one of the marsh restoration project. These tests will inform the final design of the restoration.

In May, using a barge (photo left by Ned Stone), the Corps staff conducted dilatometer tests in Dyke Marsh to measure different layers of soil and soil strength for building the foundation of the breakwater in the south marsh. Building a breakwater is expected to be phase one of the marsh restoration project. These tests will inform the final design of the restoration.

In July 2016, NPS signed an agreement on restoration design with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and in September, NPS had a “Rapid Review Team” presentation, precursor to the “Design Advisory Board,” required for projects costing over $1 million.

On March 28-30, 2017, NPS and the Baltimore District/Corps of Engineers hosted a two-day value analysis to clarify development concepts and to further refine the project plans, including the alignment of the proposed breakwater and location of off-shore sills.

On March 7, 2017, the NPS Design Advisory Board (DAB) approved the restoration project. The DAB reviews, comments on and if found sufficient, recommends construction projects costing over $500,000.

On May 21, 2017, the George Washington Memorial Parkway office of the National Park Service submitted a joint permit application to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District.

Restoration of the Marsh

For many years, the Friends of Dyke Marsh have advocated for the stabilization and restoration of the marsh. Two U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) studies found that the marsh is eroding and could be completely gone by 2035.

Fortunately, the National Park Service prepared a restoration plan, described below, and contracted with Coastal Design and Construction to build a breakwater and five sills to stabilize the marsh and encourage sediment accretion.

In November 2022, Coastal Design and Construction completed that work. The following is a brief chronology of the stabilization and restoration work.

Permits

In September 2017, the Fairfax County Wetlands Board, on a five to zero vote, approved a wetlands permit. On March 27, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission (VMRC), on a five to two vote, approved a permit for NPS to begin part of the Dyke Marsh restoration project. Generally, the permit application had two parts: (1) construction of a 1,500-foot breakwater to replicate the former promontory that protected the marsh and (2) restoration of 5.45 acres of wetland lost to dredging. VMRC approved the 1,500-foot riprap breakwater and stipulated that work on that could begin soon.

However, citing concerns about the impacts to submerged aquatic vegetation, VMRC only approved 1.5 acres of restoration, about one fourth of what NPS sought approval for and a small fraction of the 40 acres originally envisioned in phase one of NPS’s 2014 restoration plan, a plan that also envisions restoring up to 150 acres in future phases.

“We are very disappointed,” said Doug Jacobs of NPS’s National Capital Region office. “Restoring one and a half acres falls far short of our goal and it does not meet the Congressional directive to restore Dyke Marsh. Restoration was also a key purpose of the Hurricane Sandy grant. Nonetheless, we still hope to advance the project.”

In addition to Jacobs, FODMers Glenda Booth, Katherine Wychulis and Jessie Strother gave supportive testimony at the hearing. No one opposed the application at the hearing.

Click here to read the statements of the three FODM representatives to VMRC: Glenda Booth - Katherine Wychulis - Jessie Strother

On May 28, 2019, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission unanimously approved a permit modification authorizing the National Park Service to start phase two of restoration. Under the revised permit, the contractor will build a rock sill at the three-foot contour offshore of the southern marsh shoreline just north of the breakwater currently under construction. The sill will have gaps so that water and aquatic organisms will flush in and out with the tides. Because the sill will impact some submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), NPS is required to mitigate those impacts by funding a submerged aquatic vegetation project at a cost of $160,000 at, as of August 2019, an undetermined location within the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

As of early August, the submerged portion of the breakwater was about 90 percent completed; the part visible at low tide is around one-third completed.

Dyke Marsh Restoration, Phase 1 Is Completed

In February 2020, the marine engineering firm that contracted with the National Park Service to begin Dyke Marsh restoration completed phase one. Coastal Design and Construction, Inc., built a 1,500-foot breakwater and a sill in the south marsh. The breakwater is designed to replicate the former protective promontory removed by dredgers who hauled away over half of Dyke Marsh between 1940 and 1972.

Coastal Design and Construction has a contract with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District. Managers estimate that the project could take up to 18 months.

The breakwater is the first stage of restoration. U.S. Geological Survey and National Park Service (NPS) studies identified a breakwater in the southern marsh as the top restoration priority. The breakwater is designed to replicate the historic promontory removed by dredgers between 1940 and 1972. Destroying the promontory altered the hydrology of the marsh. The breakwater would “redirect erosive flows in the marsh, particularly during strong storms and would re-establish hydrologic conditions that would encourage sediment accretion,” says the NPS 2014 plan.

Dyke Marsh Restoration, Phase 2 Is Approved

On June 22, 2021, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission unanimously approved the National Park Service’s permit to construct 1,720 linear feet of rock sill in Dyke Marsh, effectively extending the current sill northward. This is considered to be phase two of the restoration and stabilization project. On November 4, the National Park Service awarded a contract for phase two to Coastal Design and Construction, Inc.

Two Phases of Restoration Completed

In November 2022, Coastal Design and Construction completed construction of sills north of the breakwater. These structures are intended to provide buffers against storms, stem erosion and encourage accretion in the marsh.

Dyke Marsh Restoration, A Chronology

1930s

Smoot Sand and Gravel acquired 650 acres of Dyke Marsh from Bucknell University.

1930s

1940 - 1972

Smoot Sand and Gravel dredged least 270 acres of sand and gravel and the swamp forest wetlands of the promontory on the south end of Dyke Marsh and built the Haul Road.

1959

Congress passed and the President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law P.L. 86-41 on June 11, a bill adding the Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve to the National Park system "so that fish and wildlife development and their preservation as wetland wildlife habitat shall be paramount." Congressman John Dingell (D-Michigan), one of the authors of the legislation, stated, "We expect that the Secretary will provide for the deposition of silt and waste from the dredging operations in such a way as to encourage the restoration of the marsh at the earliest possible moment."

1959

1974

Congress passed and the President signed P.L. 93-251 which authorized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to assist NPS in planning, designing and implementing the restoration of the “historic and ecological values of Dyke Marsh.”

1975

Smoot Sand and Gravel relinquished their mining rights.

1975

1977

The National Park Service prepared an environmental assessment proposing management options for Dyke Marsh, including "attempt re-establishment of portions of the dredged marsh."

2004

The University of Maryland, Center for Environmental Science, Appalachian Laboratory held a workshop titled, "Should We Restore Dyke Marsh"?

2004

2007

Congress passed the Water Resources Development Act which directed NPS to restore Dyke Marsh.

2009

The U.S. House of Representatives approved H. Res. 701, introduced by Congressman Jim Moran (D-VA), recognizing Dyke Marsh as a unique and precious ecosystem that should be conserved, protected and restored.

2009

2010

The U.S. Senate approved S. Res. 297, introduced by Senator Jim Webb (D-VA), recognizing Dyke Marsh as a unique and precious ecosystem that should be conserved, protected and restored.

2010

The U.S. Geological Survey study found that Dyke Marsh will disappear in 20 to 30 years without action. Analysis of the Deconstruction of Dyke Marsh, George Washington Memorial Parkway, Virginia: Progression, Geologic and Manmade Causes, and Effective Restoration Scenarios. By Ronald J. Litwin, Joseph P. Smoot, Milan J. Pavich, Helaine W. Markewich, Erik Oberg, Ben Helwig, Brent Steury, Vincent L. Santucci, Nancy J. Durika, Nancy B. Rybicki, Katharina M. Engelhardt, Geoffrey Sanders, Stacey Verardo, Andrew J. Elmore, and Joseph Gilmer

2010

March 27, 2013

The Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority announced a statement of findings, making $2.5 million available to NPS for construction of the first phase of restoration a promontory in the southern part of the marsh.

October 3, 2013

The U.S. Geological Survey published a follow-up report, concluding that ". . . Dyke Marsh presently is in its late stages of failure as a freshwater tidal marsh system . . . In the absence of human efforts to restore the equilibrium between marsh and tide, and equilibrium to the other natural forces acting on this wetland, Dyke Marsh likely will continue to accelerate its degradation, erosion, and fragmentation until it is gone. This likely will occur prior to 2035 AD." Rates and Probable Causes of Freshwater Tidal Marsh Failure, Potomac River Estuary, Northern Virginia, USA. By Ronald J. Litwin, Joseph P. Smoot, Milan J. Pavich, Erik Oberg, Brent Steury, Ben Helwig, Helaine W. Markewich, Vincent L. Santucci and Geoffrey Sanders. See the report.

October 3, 2013

October 25, 2013

U.S. Department of Interior Secretary Sally Jewell announced the award of a $24.9 million grant to the George Washington Memorial Parkway to restore Dyke Marsh.

January 2014

NPS issued the draft Restoration and Long-term Management Plan/Draft Environmental Impact Statement and had a public comment period from January 15 to March 18. During the comment period, NPS received around 300 comments, most of which were supportive.

January 2014

February 26, 2014

NPS held a public meeting and presented the draft final environmental impact statement (EIS) and restoration plan. Around 100 people attended.

October 9, 2014

The National Park Service published the final Dyke Marsh Restoration and Long-term Management Plan in the form of an environmental impact statement.

October 9, 2014

July 2015

Officials of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the National Park Service (NPS) signed an interagency agreement on preparing a restoration plan.

Fall 2015

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE) started preparing engineering plans for restoration, after a September 28-29 "kickoff" meeting with NPS. NPS and COE officials predict that the design phase will take 12 months.

Fall 2015

October 15, 2015

The National Park Service issued a press release announcing that the COE is preparing engineering plans and that geotechnical drilling in the marsh will start on October 19. The drilling will provide sediment samples from the marsh and help determine some features of the foundation for the design of the promontory, phase one of restoration. The release states, " The restoration efforts are anticipated to begin summer 2017 and expected to take four years." NPS and COE announced that the "project team is looking for potential sources of clean dredged material at no cost for restoration purposes." For information, contact Rolando Sanidad, project manager, at 410-962-2668 or Roland.Sanidad@usace.army.mil.

Once the design work is completed, NPS will have to get several permits.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers signed the programmatic agreement for section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.

December 2015

The Baltimore District Corps of Engineers created a website on Dyke Marsh restoration here.

December 2015

February 2016

The COE conducted a bathymetric survey in Dyke Marsh.

May 2016

The COE conducted dilatometer tests in Dyke Marsh to measure different layers of soil and the soil strength for building the foundation of the breakwater in the south marsh.

May 2016

June 29, 2016

Robert Vogel, Regional Director, National Capital Region, National Park Service, signed the record of decision for the Dyke Marsh Wetland Restoration and Long-term Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement.

July 2016

NPS signed an agreement on restoration design with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

July 2016

September 2016

NPS had a rapid review team presentation, precursor to the design advisory board, required for projects costing over $1 million.

March 7

The NPS Design Advisory Board (DAB) approved the restoration project.

March 7

March 28, 2017 - March 30, 2017

NPS and the Baltimore District/COE hosted a two-day value analysis to clarify development concepts and refine the projects plans.

May 21, 2017

The NPS submitted a joint permit application to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Norfolk District.

May 21, 2017

September 12, 2017

On a five to zero vote, the Fairfax County Wetlands Board approved the National Park Service's restoration permit application.

September 30, 2017

The Baltimore District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers awarded a construction contract to Coastal Design and Construction, Gloucester, Virginia

September 30, 2017

March 27, 2018

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission on a five to two vote approved a permit, with conditions, to build a breakwater and begin limited wetlands restoration.

July 2018

Coastal Design and Construction Inc., a Gloucester, Virginia, business, under contract with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District, started construction of the breakwater.

July 2018

February 2019

By February 11, Coastal Design and Construction had lowered 3,800 mattresses from a barge to the river bottom (using crane, photo at right), stacked them one on top of another and placed armor stone on top.

March 1, 2019 - July 1, 2019

The contractor temporarily suspended work because construction permits have seasonal limitations to protect fish, birds and other wildlife during their breeding and migration season.

March 1, 2019 - July 1, 2019

May 28, 2019

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission approved a permit modification authorizing the National Park Service to start phase two of restoration, a rock sill north of the breakwater with windows to allow for tidal flushing.

September 2019

The contractor started phase 2 of restoration, construction of a sill north of the breakwater.

September 2019

February 2020

The contractor completed construction of the breakwater and sill.

June 22, 2021

The Virginia Marine Resources Commission unanimously approved a permit to extend the sill by 1,720 linear feet.

June 22, 2021

November 2022

Coastal Design and Construction completed the construction of additional sills north of the breakwater.